Fighting Fire with John Lofting’s Patented ‘Sucking Worm Engine’

Up to 1666, the quality of firefighting in London was poor. Despite fires being a regular occurrence in the city, there were no fire brigades, and people didn’t give much thought to the dangers of fire to human life or property. This radically changed after the Great Fire. After beginning in a baker’s shop on Pudding Lane on 2nd September, the fire raged for four days as a strong easterly wind caused it to spread rapidly across London’s densely-packed, timber-structured and thatched buildings.

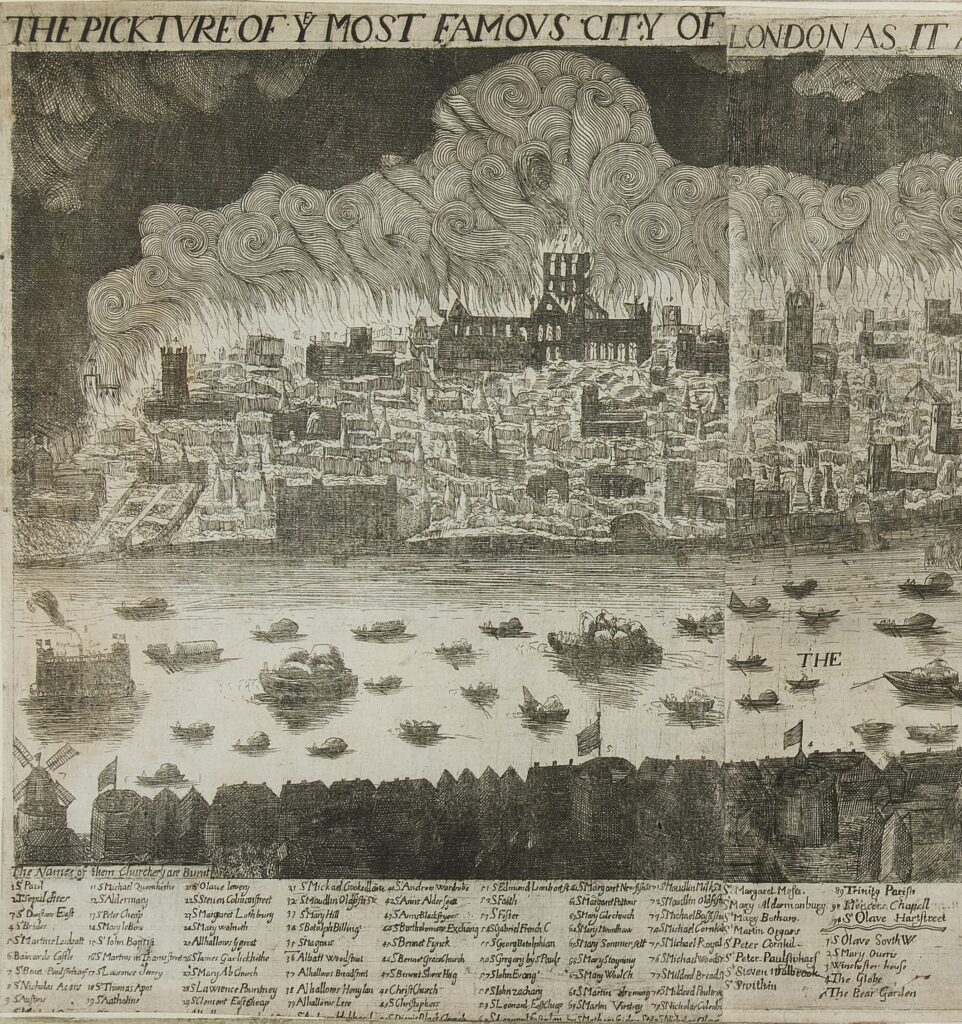

Detail from an engraving of the City ablaze on 2nd September 1666, with a list of churches destroyed underneath [Harley Collection, vol. 4]

Remarkably, there were few recorded deaths from the fire itself, but estimates put the destroyed property value at a staggering £10,000,000 (£1.5 billion in today’s money). Some 13,200 houses were destroyed, along with 87 parish churches, the Royal Exchange, the Guildhall, and St. Paul’s Cathedral. South of the river was spared, but only because another fire thirty years earlier had already destroyed a section of London Bridge, halting the spread of the Great Fire.

Oil painting of the Great Fire of London [LDSAL 305; Scharf XLV], gifted to SAL by Sir Henry Englefield, FSA, 1799

Details of badges of insurance companies. Metal plaques with these emblems were placed high-up on buildings as proof of their insurance against fire damage.

The demand for fire-fighting equipment accelerated technological innovations. In particular the fire engine, which had previously been crude and ineffective, became increasingly ingenious. The Dutch engineer and entrepreneur John Lofting (c.1659–1742, originally Jan Loftingh) was probably the first person in England to advocate the use of a wired suction hose. Called a “sucking worm engine“, Lofting’s invention could carry water over distances and throw it as high as 400 feet. The engines were used at several royal palaces, and were even praised by Christopher Wren.

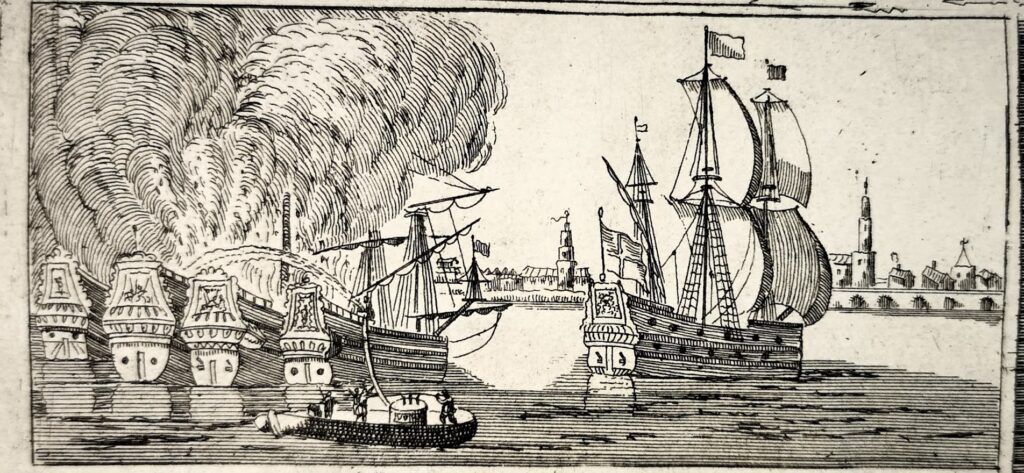

The Society holds two engravings of Lofting’s sucking worm engine in a volume of prints & drawings collected by Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford, and purchased by the Society after Earl Harley’s death in 1741. The larger of the two engravings shows the fire engine in operation in a variety of scenes annotated with letters and a key. It depicts various ways the sucking worm can be used, including fighting fire on different stories of buildings, in distilleries and on ships.

Detail of the sucking worm engine being transported by boat to put out a fire on a galley

Famous 18th-century London landmarks – such the Royal Exchange and the top of Monument – are also featured with the water reaching the top with ease. There is even a depiction of the watering of a formal garden, promoting alternative uses for the machine.

John Lofting, whose medallion portrait is at the far-right of the engraving, was a native of the Netherlands who came to England before 1686. He was a merchant and manufacturer of engines and he became a citizen of London in 1699. His patent was for the sole making and selling of ‘an engine for quenching fire, the like never seen before in this kingdom.’ The inclusion of a distillery in this image is probably not a coincidence as he also marketed an engine for ‘Starting of Beer and other Liquors’. After 1696 nothing is known of Lofting’s engines and production may have ceased. Patents only lasted for fourteen years, so after 1704, the field was open to other competitors. His other patent for a horse-powered thimble knurling machine appears to have proved more successful. In 1700, Lofting moved his operations to Great Marlow in Buckinghamshire to better utilise the power of the water wheel, increasing production of over 2 million thimbles per year.

Detail of the sucking worm engine used to quell a distillery fire

Following Lofting, inventor Richard Newsham (d.1743) patented his “new water engine for the quenching and extinguishing of fiers” in 1721 and 1725, which dominated the market in England and continued to be produced by his company until into the 1770s. Newsham’s engine had two single-acting pistons and an air vessel placed in a tank, which formed the frame of the machine. It was pulled by a cart and the pumps were manned by teams of 4 to 12 men, delivering up to 160 gallons of water per minute at up to 120 feet. Such was the reputation of Newsham’s engine, it even made its way overseas to Williamsburg, Virginia after the Capitol Building was destroyed by fire in 1747, and colonists decided a proper fire engine was a worthy investment for a settlement largely constructed in timber.