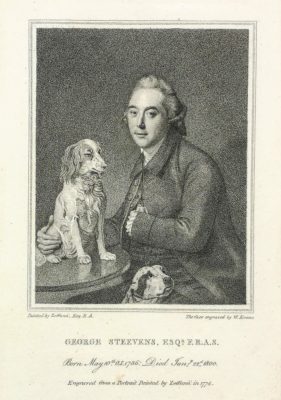

Engraving of George Steevens from a portrait dated 1774 [SAL prints & drawings collection]

The Shakespeare commentor George Steevens (1736-1800) was well-known for playing malicious pranks on his critics. Though delighting in deceiving others, Steevens was likewise conscious about the potential to end up the victim. He wrote scathingly about two contemporary literary discoveries that caused sensations when exposed as frauds – the poetry of Thomas Rowley (a 15th-century monk invented by the young poet Thomas Chatterton), and William Henry Ireland’s Shakespeare forgeries.

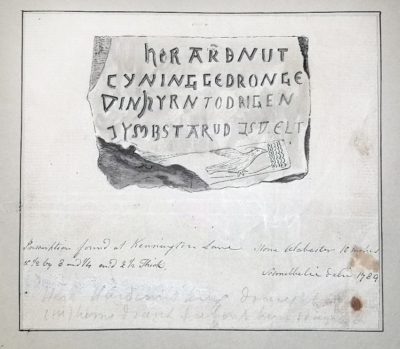

Drawing of the stone by Jacob Schnebbelie, 1789 [SAL prints & drawings collection]

stone carved with an Anglo-Saxon inscription: “Here Hardcnut drank a wine-horn dry, stared about him, and died.” The shopkeeper alleged it was found in Kennington Lane, where the King Harthacnut’s palace was said to have been located. Gough believed he had found the lost gravestone of Harthacnut (son of Cnut the Great, king of England, Denmark and Norway) who died in 1042.

Gough had fallen straight into Steevens’ trap. The “Viking gravestone” was of course a prank – Steevens’ had a slab of marble engraved with some Anglo-Saxon words and deliberately planted in the shop window for Gough to spot. And, just as planned, Gough reported his “discovery” with great excitement to the Society. He employed Society draughtman Jacob Schnebbelie to make a careful copy of the inscription.

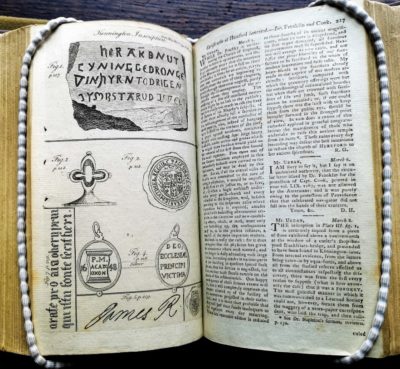

The stone as part of an engraved plate in The Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. lx, pt. 1 (1790) [SAL Library collection]

Schnebbelie’s drawing was engraved by James Basire and sent to The Gentleman’s Magazine for publication, and at Gough’s instigation, a paper on the significance of the stone was read at a Society meeting by Rev. Samuel Pegge FSA[1]. It was time for the prank to be publicly unveiled to the unsuspecting Society. Steevens’ wrote into The Gentleman’s Magazine himself and revealed the gravestone to be a fake[2], much to the embarrassment of Gough, Pegge, and the others who were taken in. Fortunately for the Society, the deception was revealed before Pegge’s paper could be published in the Society’s journal Archaeologia.

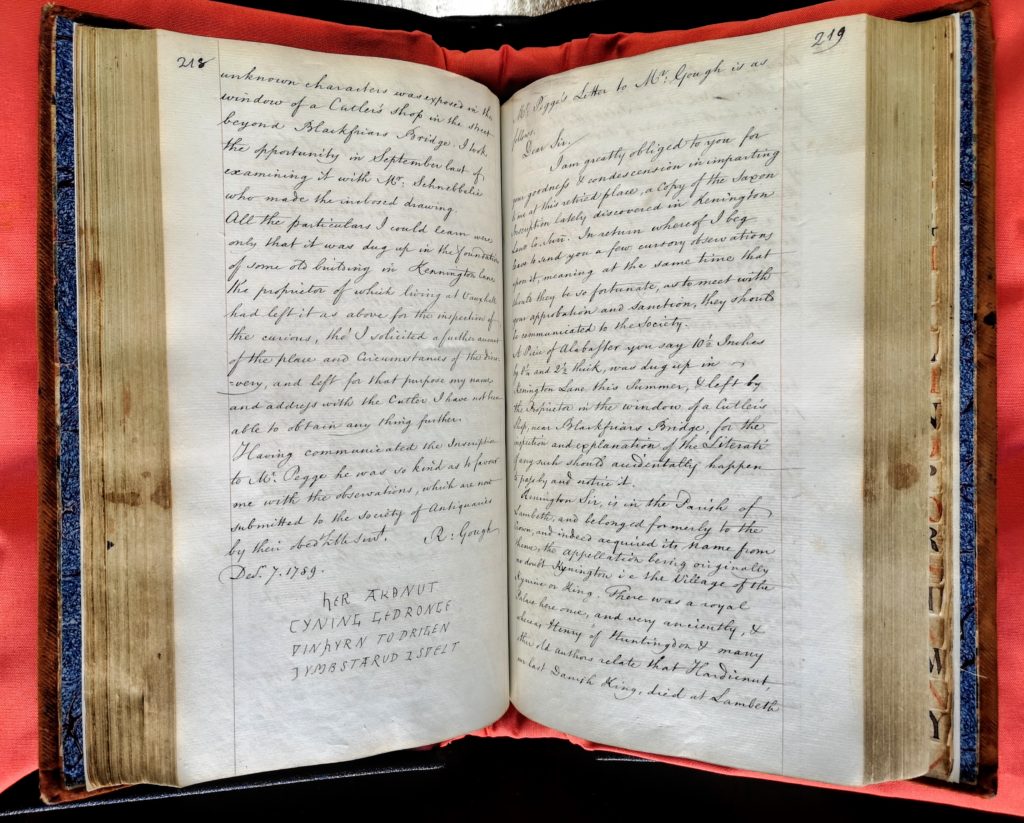

Richard Gough’s account (read at the Ordinary Meeting of 10th Dec 1789) and the inscription drawn into the Society’s Minute Book, followed by Pegge’s observations, which conclude: “I have no objection to the genuineness of the inscription… & therefore do receive it without further hesitation…” [SAL/02/023]

It may hardly come as a surprise that Steevens’ joke did not go down well amongst the Antiquaries. He was swiftly discredited by the archaeological community but nonetheless remained thrilled with his triumph in fooling the Director. Steevens presented the stone to Sir Joseph Banks FSA, and Banks delighted in showing it off to assemblies at his house in Soho Square.

[1] Ordinary Meeting of 10th December 1789, Minute Book XXIII

[2] The Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. lx (1790), pt. 1, pp.217-18; pp. 290–92