Something famous occurred at Stonehenge over two centuries ago which we might call the Great Fall. Three of the largest megaliths – a complete trilithon – collapsed, the first time any such event was recorded, and one of only three occasions on which stones are known to have fallen at the site in modern times. The incident is often referred to, but there has been no comprehensive review of what happened or of its significance since it was described at the time.

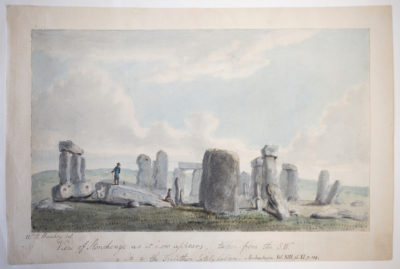

Society of Antiquaries of London’s watercolour before the Fall in January 1779.

In 2020 the Society of Antiquaries tweeted two watercolours from its collections, said to show Stonehenge before and after the Fall. They were new to me, but it was clear that they must have been the originals from which engravings were made for reproduction in Archaeologia for an article about the event. Once covid rules allowed, I went to London and Dunia Garcia-Ontiveros, Head of Library and Museum Collections, and Becky Loughead, the Society’s Librarian, got them out for me to see.

They had been trimmed and mounted on paper, before being pasted in the 1850s or 60s into an album known as the Wiltshire Red Portfolio. The reproductions – engraved by J Basire – are very close, including the captions, the Before view (“as it appeared before the 3d. of January 1797”) credited to Revd T Rackett and the After (“as it appears”) to WT Beechey.

Society correspondence at this time was carefully copied into day books. This reveals that William George Maton had visited Stonehenge within a week of the Fall, and had written on three occasions, each time changing details of what he had learnt. His final letter was reproduced verbatim in Archaeologia – the first description of any part of Stonehenge in the Society’s journals. On November 15 he wrote to say that since this last letter had been read, he had “been fortunate enough to procure two drawings” showing Stonehenge before and after the Fall, which he offered as a gift. They were perfectly copied by James Basire, though I don’t know if this was the father (1730–1802), who advertised himself as a “History, Portrait, and Architecture

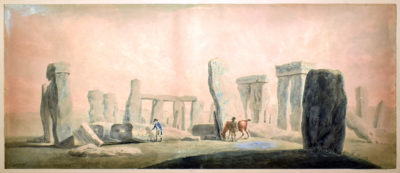

Society of Antiquaries of London’s watercolour after the Fall.

Engraver, and Engraver to the Society of Antiquaries”, or the son (1769–1822), who engraved Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s Ancient History of South Wiltshire (1812) including a plan of Stonehenge, and views of Stonehenge for Hoare’s The Modern History of South Wiltshire (1826).

Shortly before I saw these drawings, I happened to be giving a talk in Salisbury and dropped into the museum. Here Adrian Green, Director of the Salisbury Museum, showed me another pair of watercolours showing Stonehenge before and after the Fall, also new to me – I suspect all four will be new to many archaeologists, as until now none of them had been exhibited for some time.

Both of the Salisbury watercolours are signed T Rackett, and were given to the museum by a Mrs Macgacken of Kent in 1887. Even back then it seems there was no awareness that there were two sets, as this one was said to have been copied for Archaeologia – when in fact it was the London pair that were engraved for the journal.

Have we got Stonehenge wrong?

There are many questions. How is it that we have three watercolours ascribed to Thomas Rackett and a fourth, identical in style to its partner, to another artist? Were two really drawn before the fall and two after, or were the pairs imaginatively conjured as a basis for engravings to sell? Who were Maton, Rackett, Beechey and Basire? And perhaps most importantly, what do we know about the Fall? What can these watercolours tell us about Stonehenge?

I’m still researching and I’d be grateful for any help, but let’s look at the drawings.

Salisbury Museum’s watercolour before the Fall signed by T Rackett

All show the monument looking from the west or south-west, and the drawings within each pair are the same in finish, shape and size. These things differ between the pairs (the Salisbury drawings are much larger), but there is another curious difference. When apparently two artists created the two London drawings looking every bit as if they were made by the same person, we might expect the views to be the same – Beechey (who drew fallen stones) copying the before view but altering three of the stones. Yet the views are different, the second version arguably angled for a better view of the fallen stones and implying it was drawn on the spot.

The two in Salisbury on the other hand, both by Rackett and which we might have expected to have been separately created, are identical except for the centres. He’s made an exact copy of the before view and changed the now fallen trilithon. The fallen stones have the same sort of detail as the others and look convincing. But if you look closely you can see that stones revealed by the fall, hidden in the first drawing, have been blocked in with less detail, as Rackett might have done if he’d had to imagine them.

I think rounding up as many views of the fallen trilithon as possible will help here. Which were drawn at Stonehenge, and which were imagined, or copied from other artwork? These stones offer a perfect record of damage done at the site by souvenir hunters. In 1796, and for millennia before, the great lintel was for all practical purposes out of reach. From early in 1797 until it was re-erected in 1958, it was on the ground, a sitting target for the sort of visitor we see in the first Salisbury watercolour – bashing away under the directions of a gentleman.

Salisbury Museum’s watercolour after the Fall signed by T Rackett

And why does this matter? We’ve long known that visitors damaged the stones. People complained about it at the time it happened, and what we might call a rural myth went round that you could hire a hammer in Amesbury for the purpose – something that no one has been able to prove was actually the case. But we had little idea how much damage was really done.

In 2011 English Heritage commissioned a laser survey of the stones. This revealed that what appears to be souvenir damage is in fact quite extensive. The fallen trilithon holds the key to this. Any difference between the stones before the Fall in 1797 and later, has to be due to visitor damage during those 160 years they spent on the ground. Looking at the two watercolours showing the Fall, at William Stukeley’s illustrations of this trilithon in the early 18th century, and at the lintel today, it seems the damage was strong, turning a sharp-angled and finely carved stone into a rounded pillow. It may be that we’ve been underestimating the original monument, whose stones may have been more carefully dressed and shaped than we think.

I’ve written more about this recent damage to stones in my new book, How to Build Stonehenge (Thames & Hudson). It’s a growing area of research: I didn’t know about these watercolours until after the book had gone to press.

With thanks to Adrian Green from The Salisbury Museum for permission to use the two images of their Stonehenge watercolours in this post.